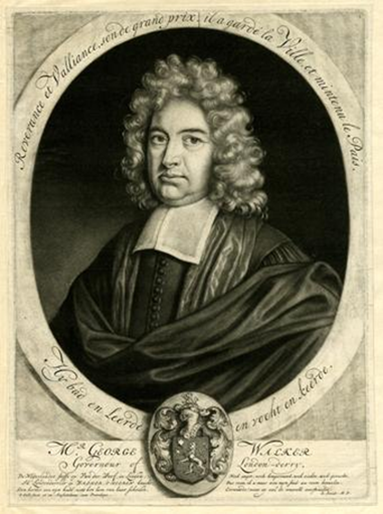

Figure 11 Reverend George Walker

With the stand off that started with the closing of the gates by the apprentice boys on the 7th December, having come to a close, the siege itself was underway. With the Jacobite threat ever present, those within the walls of Londonderry were required to muster a force of their own to repeal and thwart any advances made against their city. As such, both pre-existing and recently established regiments mustered companies of around sixty men who in turn would select a Captain, who would then designate a Colonel for the regiment. The regiments, with a total of some 117 companies are recorded as follows;[1]

No.companies

Colonel Walker (Rev George) to Sir A. Rawdon’s regiment (former dragoon regiment) 15

Major Baker to be Colonel of Lord Charlemont’s Regiment 25

Major Crofton to be Colonel of Canning’s Regiment 12

Major Mitchelburne to be Colonel of Hamilton’s Regiment 17

Lieutenant- Colonel Whitney to be Colonel of Hamilton’s Regiment 13

Major Parker to Command the Coleraine regiment 13

Captain Hamill to be Colonel of a regiment 14

Captain A. Murray to be Colonel of horse 8

Walker records a rough estimate of the population of the city at the outbreak of the siege;

This was our complement after having form’d our selves, as above mentioned ; but the Number of Men, Women and Children in the Town, was about Thirty thousand. Upon a Declaration of the Enemy to Receive and Protect all that would desert us, and return to their dwellings. Ten Thousand left us.[2]

Developments were taking place outside of the city too. The first Duke of Berwick, James FitzJames (illegitimate son of King James)[3] writes of James’ departure and the Jacobite capture of the nearby fort at Culmore;

When leaving, the King left Momont and Hamilton in command of the armies, bringing Mr de Rosen with him. After the King’s departure, we resolved to approach Londonderry, to block it, while waiting for that which was necessary for the siege. Momont, Hamilton, Pusignan and I went forward with four hundred infantrymen, the Tirconel Cavalry, and that of the Dungan Dragoon, bringing our sum to around seven hundred cavalrymen. We made our quarters near the Cullmore fort below Derry (Londonderry) on the same river; the captain of the fort surrendered first, although we had nothing with which to conquer it.[4]

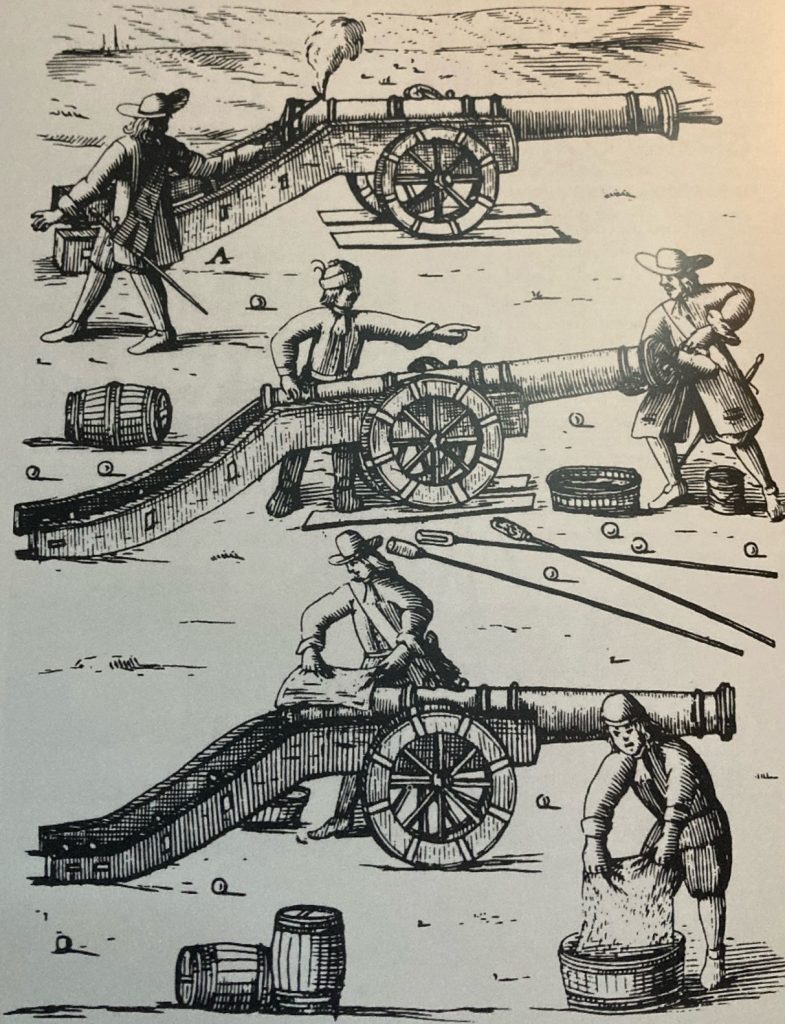

With the rather lacklustre result of his appearance before the walls, James departed Londonderry for Dublin, leaving his two French Generals; de Maumont and de Pusignan with the task of taking the city. Maumont would act quickly, establishing a gun post on the east bank of the Foyle, at Stronges Orchard. Lord Louth would command 3,000 men along this eastbank, opposite Ship Quay gate, with a considerably strong detachment of men occupying Pennyburn Hill and cutting off communication between the city and Culmore Fort.[5] The Jacobites, however, were issued with the most inadequate of weaponry for siege warfare, particularly besieging such a place as Londonderry with its thick, low walls and angle bastions.[6] Whilst their mortars proved effective in destroying the morale of those behind the walls, their light cannon did little in the way to damage the walls.

With it becoming more clear to the Jacobites that the city would indeed not surrender, bombardment commenced the 21st April;

The Enemy placed a Demi- culverin, 180 Perches distant from the Town, E. B. N. on the other side the water : they play’d at the houses in the Town, but did little or no mischief only to the Market- house[7]

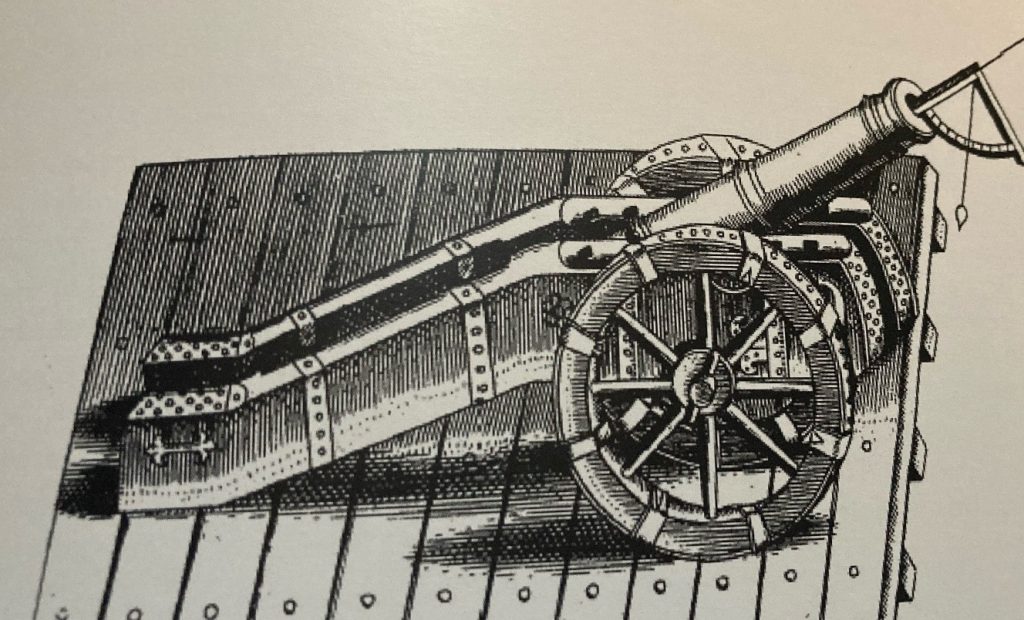

Figure 12- Gun crews firing and loading– indicative of what would have been used at Siege of Londonderry

Furthermore, on the same day as the Jacobite bombardment, the Williamites made a series of decisive strikes of their own. Accounts record that a sally lead by Colonel Adam Murray of both foot and horse made for Pennyburn village, a mile or so north of Londonderry, repealing a Jacobite attempt to take the village. This would prove to be a most significant of events for the Williamites, with both of James’ French Generals killed during the engagement. Major General Puisgan would expire this day along with Lieutenant- General Maumont who was struck down by Murray’s blade;

Colonel Murray charged through that brigade, and had that day three personal encounters with their commander, in the last of which he killed him on the spot, whom the enemy themselves confessed to be Lieutenant- General Maumont[8]

Murray, of all, he did excel,

Before, behind him, numbers fell;

His tempered steel he boldly drew,

With which the brave Maumont he slew,

And forced the rest to cry “Morbleu”![9]

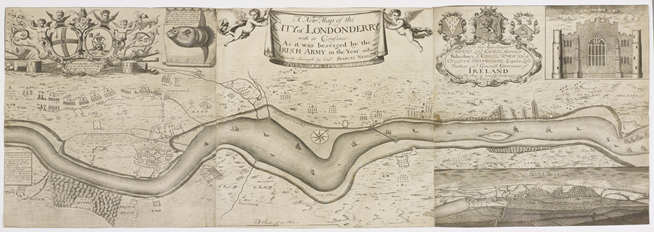

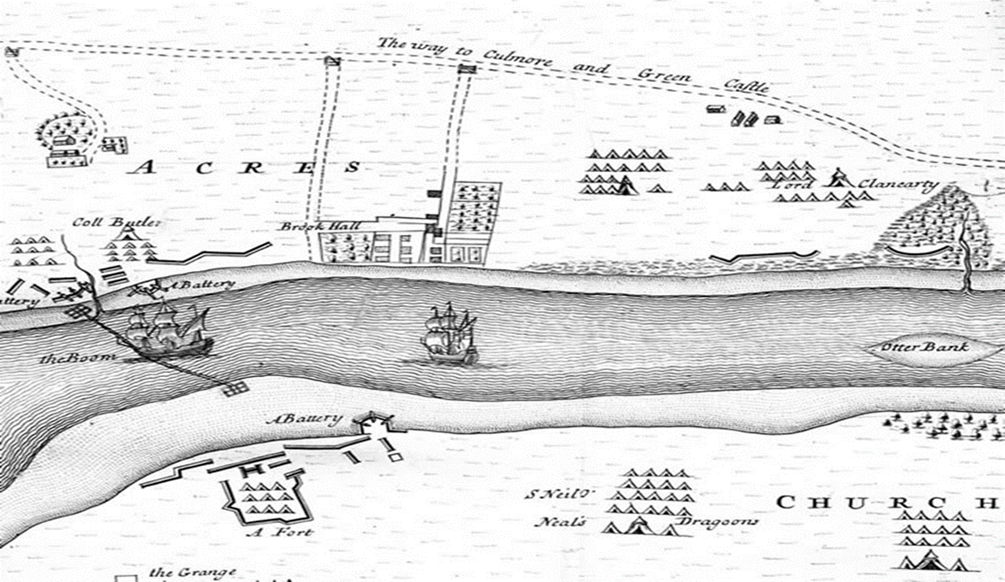

Figure 13- A New Map of the / CITY of LONDONDERRY / with its Confines; / As it was beseiged by the IRISH ARMY in the Year 1689

Two days later, on the 23rd April, the Jacobites placed “two cannon” in the lower end of Strong’s Orchard, of the east bank of the Foyle, near “80 perches from the town”, opposite Ship Quay gate. The bombardment was constant, injuring many within the city, and causing significant damage to “Walls and Garrets”. Not all was to go in favour of the Williamites. With Culmore Fort (four miles north of Londonderry) cut off from communicating with the city, it was easy prey for the Jacobites, who took the fort with little opposition. It would have been a most futile endeavour for a garrison of only three hundred men to attempt any defence. The fortress was surrendered to the Duke of Berwick.

Over the next number of days, the Jacobites continued their relentless bombardment of the city. Walker records on the 25th April;

They placed their mortar pieces in the said orchard, and from thence played a few small bombs, which did little hurt to the town… they threw many large bombs, the first of which fell into a house while several officers were at dinner; it fell upon the bed of the room they were in but did not touch any of them.[10]

The intense Jacobite bombardment continued onto the 27th with ammunition being stored within St Columbs’ Cathedral for safe keeping. Ash recounts the relentless bombardment;

The bombs played hotly all night; eighteen were shot into the city, one fell on Mr Long’s house and killed a gentlewoman of eighty years old, a Mrs. Susannah Holding, and hurt many others.[11]

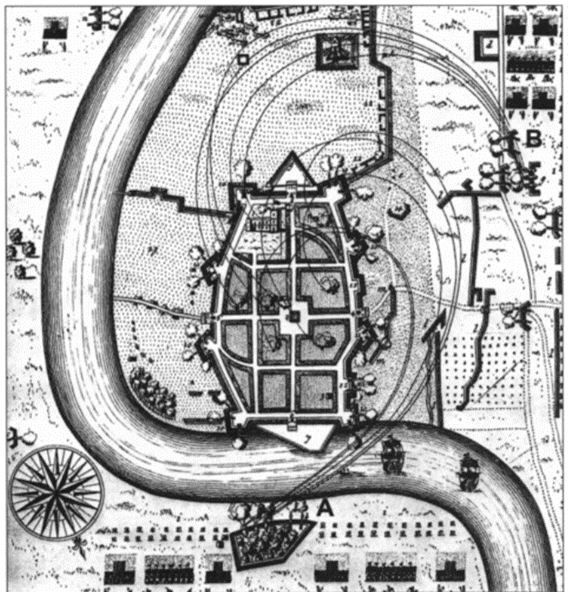

Figure 14- Jacobite gunner

The Jacobites, who had entrenched themselves at Windmill Hill, 500 yards or so from Bishop’s Gate, “begin a battery; from that they endeavour to annoy our walls”[12]. Governor Baker ordered the detaching of ten of every company to attack the besiegers. Mackenzie records the impatience of some of the defenders,“ the men were impatient, and ran out of their own accord, some at Bishop’s Gate, other at Ferryquay Gate”.[13] They pursued the Jacobites “so close, that they came to club-musket with it”. Ultimately, Windmill Hill would be another important victory for the Williamiates, killing the Jacobite Brigadier General Ramsay, and taking “four or five colours, several drums, fire-arms, some ammunition and good store of spades, shovels, and pick- axes”. It was only with the victory at Windmill Hill did Williamites learn Culmore Fort had fallen. Mackenzie writes;

Captain Noble and others found several letters in the pockets of the slain, giving them some intelligence, particularly about the surrender of Culmore.

Baker, acting on advice from his officers, resolves to better defend Windmill Hill from future attacks. He agrees to drawing a line across the hill from the bog to the water, setting men to securing the hill with redoubts to better defend from enemy cannon fire.

Further Williamite sallies continued. One of particular note saw further heroics from Adam Murray, who upon witnessing a party of 200 men under the command of Lieutenant-Colonel Blair being cut off from the city by a large body of Jacobites, “rides along Bog-street, and through a party of the enemy behind a ditch fired incessantly at him, he went on to the place to warn them of the danger”.[14]

Figure 15- map of the siege showing position of mortars

The Jacobites, with their failures to take Pennyburn Village, and Windmill Hill, move their camps to Pennyburn Mill, Stronges Orchard and Ballyoughry. These camps, whilst allowing for a significant degree of fire into the city, also have the added benefit of reducing intelligence falling into enemy hands. Londonderry was completely surrounded by Jacobite positions come the 15th May. Their guns were brought to Ballyoughry, “with a design to strike the greater terror into the hearts of the besigied”.[15] About this time, several Williamite Captains; Noble, Cunningham and Archibald with 100 men capture the Jacobite held fort at Creggan. However, on their return to the city, they are set upon by enemy cavalry. Captain Cunningham and sixteen men are taken prisoner and killed on the orders of Colonel Piers Butler, Lord Galmoy.

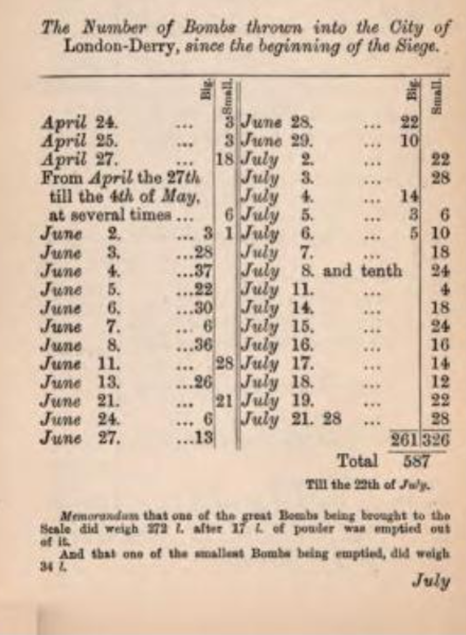

For much of the siege, the Jacobites were issued with inappropriate means of besieging such a settlement as Londonderry with its thick, low walls and angle bastions. Fortunes would change for the Jacobites with the arrival of heavy siege guns and mortars on the 30th May. Matthew Plunkett, the 7th Baron Louth, and Lieutenant-General Bernard Desjean, Baron de Pointis are charged with bombarding the city with the newly arrived artillery pieces across the right bank of the Foyle. Even still, matters were not straightforward, with de Pontis’ inspection of the pieces revealing that the fuses for the bombs did not fit, some were too large, others too small.[16] Furthermore, de Pontis expected somewhere in the region of 500 shells for the siege, but only received 120.[17] However, with the matter solved, bombardment commenced proper. The mortars alone would fire close to 600 rounds into the city throughout the siege.

Figure 16- canon on gun platform

With time ever pressing on, and the increasing likelihood of a relief force from England, the Jacobites made steps to curtail any Williamite attempt to break the siege. De Pontis, a renowned military engineer, built a boom across the Foyle at the narrowest point of the river at brookhall, made of fir beams. Additionally, gun ports were constructed either side of the boom. Walker writes; “they draw their guns to Charles-Fort, a place of some strength upon the narrow part of the river, where ships were to pass; here they contrived to place a boom”.[18]

Figure 17- Marshall de Pontis

Figure 18- shows the boom on the Foyle along with Jacobite dragoon and Clancarty’s camps.

Bombs were thrown into the city both day and night. Between the 24th of April and the 22nd of July, they cast into the city 587 bombs, of which 326 were small and 261 were large. Of the larger, some weighed as much as 273 pounds.[19] After seven hellish weeks of almost continuous bombardment, starvation and disease, hope was literally within sight. On the 7th June, three advance ships from the fleet; HMS Greyhound, HMS Kingfisher and Edward and James, were spotted at Culmore Fort, with the aim of gathering intelligence on the condition of Londonderry and the Jacobite defences. However, the ship of Captain Gulliam, the Greyhound, in an attempt to survey the boom ran into difficulty after a failed attempt to smash the boom, is then fired upon buy the gun forts and became stuck on the sandbanks of the Foyle. “But one of them unfortunately run aground, and lay some time at the mercy of the enemies shot”.[20] The Jacobites taunted the Williamites; “The enemy called to us from their lines, to send down carpenters to mend her”.[21] The Greyhound was badly damaged after this exchange, and whilst her crew was able to set sail once again, the morale of the both the besieged and relief fleet took a mass blow.

With time once again against the Jacobites, Richard Hamilton issued orders to retake Windmill Hill. On the 4th June, roughly ten in the morning, the Jacobites attacked with both horse and foot. “The enemy approach to our works at the Windmill with a great body of foot and horse; our men ordered themselves so, that in each redoubt there were four, and in some five reliefs, so that they were in a posture of firing continually. The Irish divided their horse in three parties, and their foot in two”.[22] The horse attack at the lowest point of the river crossing, with the foot attacking the rest of the Williamite lines, with “the foot “who had also fagots of wood carried before them) attack the line betwixt the Windmill and the water”.[23] The following day, on the 4th, Mackenzie records the further Jacobite shelling of the city, with “great ones of 273lbs”.[24]

On 13th June, the rest of Kirke’s fleet was spotted on the Foyle, which “gave us at the present the joyful prospect, not only of the siege being soon raised, but of being furnished with provisions”. However, hopes were soon dashed for the besieged. Kirke’s fleet weighed anchor, and idled within the lough. “But when we saw them lie in the Lough, without any attempt to come up, it cast a cold damp on our too confident hopes, and sunk us as low as we were raised at the first sight of them”.[25]

Somehow, a messenger made his way from Kirke’s fleet, bypassing the Jacobite lines before arriving in Londonderry. A man by the name of Roche carried a letter from Kirke addressed to the Governors. He gave an account of the circumstances on the lough, such as the number of ships within the fleet, men, provisions and plans for the relief of the city. Walker would instruct Roche to return to the fleet, with a message describing the dire conditions within the city. However, such was his luck, or lack thereof, Roche was wounded by enemy fire and returned to the city. A second messenger, a man named McGimpsey reported to Murray, volunteering to deliver Walker’s message to Kirke. The letter, Mackenzie writes, was “tied in a little bladder, in which were put two musket bullets, that if the enemy should take him, he might break the little string wherewith it was tied about his neck, and so let it sink in the water”. [26] Unfortunately for the garrison, McGimspey never made it to the fleet. Whether he drowned, hit the boom or was struck by enemy fire, it is not known but a couple of days later, “they hung up a man on a gallows in the view of the city, and called over to us to acquaint us it was our messenger”.[27]

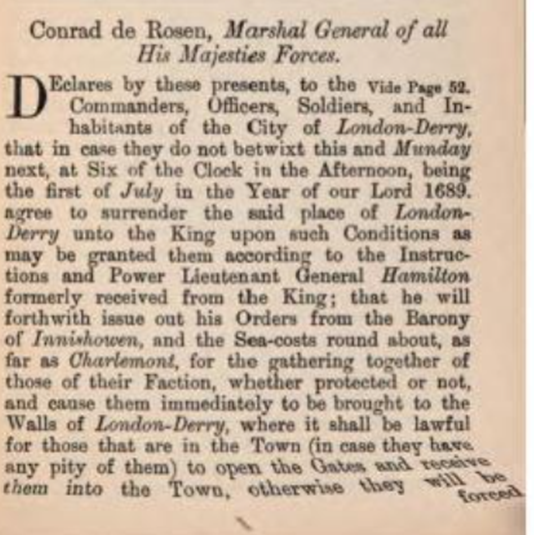

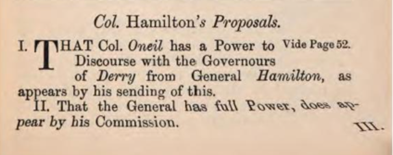

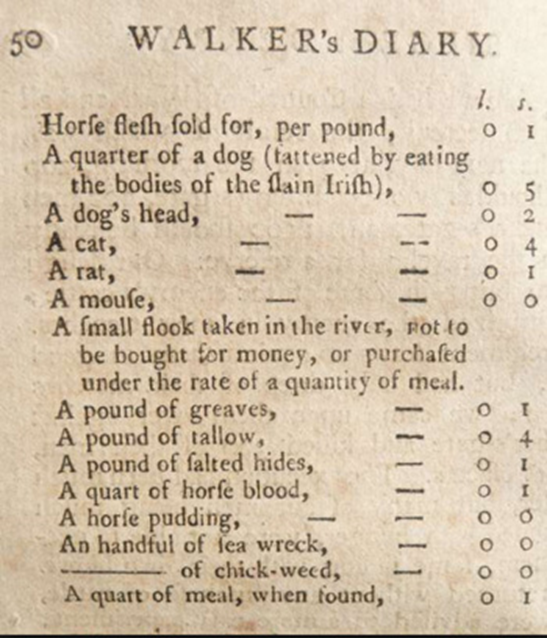

Figure 19- Marshal General de Rosen

Sometime between the 17th-24th June (accounts vary), the Marshal General of King James’ forces in Ireland, Conrad de Rosen returned to Londonderry. Rosen was not best pleased with the little progress made by the Jacobites. He ordered three mortar pieces and several pieces of ordnance to be placed on the Windmill hill side of the city, with two culverins opposite Butcher’s Gate.[28] Additionally, he orders his troops to dig a trench towards the half-bastion at the gate. On the 28th Lieutenant-Colonel Skelton, along with the recently arrived regiment of Lord Clancarty take the outworks of the city. Captains Noble and Dunbar, upon observing this, sally for Bishop’s Gate, where they proceed along the wall, allowing them to flank the Jacobites and “then thundered upon them”[29] before forcing the enemy to retreat once more from the outworks of the city. Governor Baker after suffering from illness, passed away on 30th June. Before his death, Baker called a council where it was decided that Mitchelburne, who was Deputy Governor during Baker’s bout of sickness, would succeed him as joint Governor with Walker. Baker’s death was a further blow to the already disparaged moral of the besieged who’s demise was “justly lamented by the garrison”. About this time, we are told that amongst the bombs fired upon the city, “there was one dead shell, in which a letter declaring to the soldiers the proposals made by Lieutenant General”. Included amongst this letter where Hamilton’s offer of surrender and Rosen’s threats towards unprotected Protestants outside the safety of the walls, to the effect of;

“that if we did not deliver the town to him by six the clock according to Lieutenant Gen. Hamilton’s proposals, he would dispatch his orders as far as Balishanny, Charlimont, Belfast and the barony of Inishowen, and rob and protect all protected as well as unproctected Protestants, and that they should be driven under the walls of Derry, where they should perish”.[30]

Shell that contained Hamilton’s proposals within- on display at St Columb’s Cathedral

Rosen was not bluffing. On the 2nd July, “the enemy drive the poor Protestants, according to their threatening, under our walls, protected and unprotected, men, women and children, and under great disease. There were some thousands of them, and they did move great compassion in us, but warmed us with new rage and fury against the enemy. Begging of us on their knees, not to take them into the town, but chose rather to perish under our walls.[32] Rather than guilt the garrison into submission, Rosen’s actions reinvigorated a down and out populous. When King James heard of Rosen’s plans for forcing Londonderry to surrender, he was reportedly horrified, stating;

none but a barbarous Muscovite could have thought of so cruel a contrivance[33]

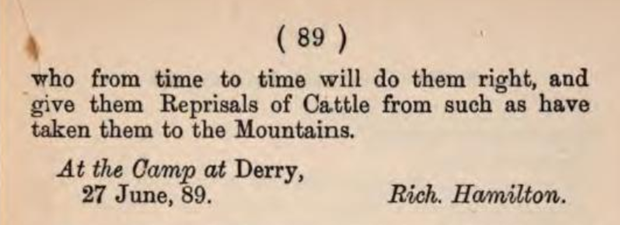

With each day that passed, hunger became an ever more perilous issue. Walker’s “food list price” has become a most infamous document of the siege outlining what was on offer with its corresponding price. Walker also writes of a rather unfortunate overweight man who garnered the suspicions of the garrison, “we were under so great necessity, that we had nothing left unless we could prey upon another: a certain fat gentleman conceived himself in great danger, fancying several of the garrison lookt on him with a greedy eye, thought fit to hid himself for three days”. [34]

With tensions and hunger growing in equal measure, the idea of surrendering the city to the Jacobites was seriously considered by the “council of fourteen”. On the 11th July, the Williamites were offered terms for a parley. With the ships having set sail from Lough Foyle and with no indication of return, the garrison agreed to the offered parley, as Mackenzie writes, “We considered most of the ships were gone, we knew not whither; provisions grew extremely scarce, and therefor to gain time, it was thought advisable to agree to it”.[36] Further news arrived from Kirke’s fleet. Ash records that a small boy from the fleet arrived with a letter from Lieutenant David Mitchell for Governor Walker with the message that, “12,000 men are landed at Lough Swilly, and that 2,000 horse are gone round to land there also”.[37] However, it would later be revealed that this was a fabrication on Walker’s part, who “transcribed it, with some additions of his own”. The reality was that Kirke had sent “some to encamp at Inch”, rather than the thousands Walker claimed.

On the 13th July, the proposed parley commenced with representatives from the city arriving in the Jacobite camp. The most important takeaway from this meeting concerned the time of surrendering, with the Jacobites who “would grant no longer time till Monday, the 15th, at twelve o’clock”. [38]

Upon hearing of the terms offered, the council decided to agree to the terms of surrender if “the enemy would give us time till the 25th July”, dearly holding out for hope of the relief fleet’s arrival. On the 14th the two sides meet once more. However, a date could not be reached, and so bombardment of the city once again resumed. Further Jacobite attacks were to follow. 16th July saw a small party attack Butcher’s Gate, and “two regiments of the enemy marched down from their camp towards Windmill-hill”.

With the continued Jacobite bombardment and sallies to the gates, hope was all but lost for the Williamites. “But the hour of our extremity was the fit season for Divine Providence to interpose and render itself the more observable in our deliverance”. On the evening of the 28th (Walker records the 30th). July, Walker preached at St Columb’s Cathedral, reassuring his congregation that “God would at last deliver them from their difficulties they were under”. At roughly seven o’clock, the relief fleet was spotted on the Foyle, anchoring at Culmore point. Ash writes triumphally of this day as “a day to be remembered with thanksgiving by the besieged in Derry as long as they live”.[39] It appeared that the prayers of the city were answered. However, the prayers did not seem to operate at full capacity, as the wind slackened, meaning the floodtide could only carry the lead ship, The Mountjoy to the boom, where it was meet with considerable Jacobite resistance from the gun forts on either side of the Foyle. Men from the Mountjoy returned fire, as “the smoke of the shot both from the land and the ships, clouded her from our sight”. It appeared to the Williamites that The Mountjoy had run aground, with shouts of “huzza” from along the shore line. However, the Mountjoy firing from her broadside, along with an increasing tide was able to break from the shore. Thus, the Mountjoy made for the boom, breaking it. The rest of the fleet, along with the Phoenix of Coleraine and the Dartmouth arrived shortly thereafter. Walker writes that, “the ships got to us, to the unexpressible joy and transport of our distressed garrison, for we only reckoned upon two days’ life”.[40]

The following morning, the Williamites observed the Jacobites abandon their positions around Londonderry, and setting for march to Strabane. They were swiftly pursued by the Williamites, and upon learning of the defeat of the Jacobites at Enniskilling, “thought fit to make haste to get further off”. After a period of 105 days, and close to 10,000 dead within the city, the siege was over. With the successful defence of the Protestant citadel garrisons of Londonderry and Enniskillen, and with the further Williamite victories at Newtownbutler, the Boyne, Aughrim and Limerick, Jacobite Ireland was finished.

The defence of Londonderry was a tremendous strategic victory for the Williamites, ultimately ending James’ ambitions of regaining his three thrones. The success of the siege gave the Williamites the much needed confidence boost and propaganda victory for their cause to restore Protestantism to crown of Ireland. The siege of Londonderry’s impact was vast, setting the course for the future of the monarchy in England, Scotland, and Ireland, but also contributed to the outcome of the greater European conflict raging between the armies of the Grand Alliance and the Sun King.

“AND THEIR CRY WAS NO SURRENDER!”

Bibliography

Primary Sources

Aicken, Joseph, Londerrias, Londonderry: John Hempton, Diamond

Ash, T., 1861. The Siege and history of Londonderry.. Londonderry: John Hempton, Diamond.

Berwick, J., 1779. Memoirs of the Marshal Duke of Berwick. Written by himself. With a summary continuation from the year 1716, to his death in 1734. In two volumes. To this work is prefixed a sketch of an historical panegyric of the Marshal, by the President Montesquieu; … notes, and … letters relative to the campaign in Flanders, in 1708, are subjoined. Translated from the French. London: printed for T. Cadell.

MacKenzie, J. and Killen, W., n.d. Mackenzie’s Memorials of the Siege of Derry.

Walker, G., 1907. Reprint of Walker’s Diary of the siege of Derry, in 1688-89. Londonderry: Printed by J. Hempton & Co.

Secondary Sources

Childs, J., 2008. The Williamite wars in Ireland, 1688-91. London: Hambledon Continuum.

Doherty, R., 2016. The Siege of Derry 1689 The Military History. Chicago: The History Press.

Macpherson, J., 1776. Original papers containing the secret history of Great Britain. London: W. Strahan and T. Cadell.

Scott, B., 2008. The great guns like thunder. Derry: Guildhall Press.

Scott, B., 2015. THE DEPLOYMENT OF MORTARS IN IRELAND UP TO THE 1689 SIEGE OF LONDONDERRY. , Ulster Journal of Archaeology, Vol. 73(Third Series).

Simpson, R., 1987. , The Annals of Derry: Showing the Rise and Progress of the Town from the Earliest Accounts On Record to the Plantation Under King James I. 1613, and … the City of Londonderry to the Present Time. Limavady: North-West Books.

Young, W.R, Fighters of Derry; Their Deeds and Descendants being a chronicle of events in Ireland during the revolutionary period, 1688-1691. London, Eyre and Spottiswoode

Wills, J., n.d. A history of Ireland in the lives of Irishmen. London: Fullarton.

Witherow, T., 1913. Derry and Enniskillen in the year 1689. Belfast: W. Mullan & Son.

Figures

Figure 1- The Relief of Derry, George Frederick Folingsby (1830–1891) Derry City and Strabane District Council

Figure2- King William III, Peter Lely, 1677, oil on canvas, National Portrait Gallery, London

Figure 3- King James II, Godfrey Kneller, 1684, oil on canvas, National Portrait Gallery, London

Figure 4-, Richard Talbot, Earl of Tyrconnel, François de Troy, oil on canvas, 1690-1691, National Portrait Gallery

Figure 5- Aunt Charlotte’s Stories of English History for the Little Ones” by Charlotte M Yonge. Published by Marcus Ward & Co, London & Belfast, in 1884

Figures 6-9- The great guns like thunder. Derry: Guildhall Press.

Figure 10- Portrait of Major Baker (courtesy of Chapter House Museum, St Columb’s Cathedral)

Figure 11- George Walker, mezzotint, Ludolf Smids, published by Jacob Gale, 1690s, National Portrait Gallery

Figure 12- Gun crews firing and loading

Figure 13- A New Map of the / CITY of LONDONDERRY / with its Confines; / As it was beseiged by the IRISH ARMY in the Year 1689

Figure 14- Jacobite gunner

Figure 15- Map of Siege of Londonderry by Captain Archibald McCullough

Figure 16- canon on gun platform

Figure 17- Portrait (gravure) de Jean Bernard de Pointis (1645-1707), chef d’escadre de la Marine royale française

Figure 18- boom on the Foyle

Figure 19- Portrait, Hyacinthe Rigaud in 1705 ,Conrad von Rosen

Figure 20- The relief of Derry, the Mountjoy breaking the boom, C. B., Illustrator

[1] R. Simpson, The Annals of Derry: Showing the Rise and Progress of the Town from the Earliest Accounts On Record to the Plantation Under King James I. 1613, and … the City of Londonderry to the Present Time (Londonderry, 1847).

[2] Walker,G Narrative of Siege of Londonderry p.30

[3] Witherow, T, Derry and Enniskillen in the Year 1689, 1931 p.

[4] Memoirs of the Marshal Duke of Berwick, Written by Himself,1779 English translation kindly provided by Eve Devlin

[5] Witherow, T, Derry and Enniskillen in the Year 1689, 1931 p116

[6]Scott,B, THE DEPLOYMENT OF MORTARS IN IRELAND UP TO THE 1689 SIEGE OF LONDONDERRY, Ulster Journal of Archaeology, Third Series, Vol. 73 (2015-16), pp. 204-218

[7] Walker,G Narrative of Siege of Londonderry p.39

[8] Mackenzie, J, A Narrative of the Siege of Londonderry (London,1690) , in W.D Killen, Mackenzie’s Memorials of the Siege of Derry, (London,1861) p.39

[9] Mitchelburn, John, 54

[10] Walker,G Narrative of Siege of Londonderry p.116

[11] Ash, T, A Circumstantial Journal of the Siege of Londonderry,1792, p. 282

[12] Walker,G Narrative of Siege of Londonderry p.116

[13] Mackenzie, J, A Narrative of the Siege of Londonderry (London,1690) , in W.D Killen, Mackenzie’s Memorials of the Siege of Derry, (London,1861) p.226

[14] Mackenzie, J, A Narrative of the Siege of Londonderry (London,1690) , in W.D Killen, Mackenzie’s Memorials of the Siege of Derry, (London,1861) p.227

[15] IDIB

[16] Macpherson,J Secret History of Great Britain from the Restoration to the Accession of the House of Hanover,1775

[17] Scott,B, THE DEPLOYMENT OF MORTARS IN IRELAND UP TO THE 1689 SIEGE OF LONDONDERRY, Ulster Journal of Archaeology, Third Series, Vol. 73 (2015-16), pp. 204-218

[18] Walker,G Narrative of Siege of Londonderry p.121

[19] Witherow, T, Derry and Enniskillen in the Year 1689, 1931 p.138

[20] Walker,G Narrative of Siege of Londonderry p.121

[21] Mackenzie, J, A Narrative of the Siege of Londonderry (London,1690) , in W.D Killen, Mackenzie’s Memorials of the Siege of Derry, (London,1861) p.232

[22] Mackenzie, J, A Narrative of the Siege of Londonderry (London,1690) , in W.D Killen, Mackenzie’s Memorials of the Siege of Derry, (London,1861) p.229

[23] IDIB

[24] Mackenzie, J, p.231

[25] Mackenzie, J, p.233

[26] Walker,G Narrative of Siege of Londonderry p.124

[27] Mackenzie, J, p.239

[28] Walker,G p.124

[29] IDIB

[30] Walker, P.126 & 127

[31] Walker, P.87-89

[32] Walker,G Narrative of Siege of Londonderry p.128 &129

[33] Zeslie, p. 100 ; Avavx, p. 257 and 309.

[34] Walker, G. p. 132

[35] Walker, G. p.132

[36] Mackenzie, J, p.244

[37] Ash, T, A Circumstantial Journal of the Siege of Londonderry,1792, p.294 Figure 20- The Mountjoy

[38] Mackenzie, J. p.245

[39] Ash, T, A Circumstantial Journal of the Siege of Londonderry,1792, p.301

[40] Walker, G. p.133

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.