“Five generations have since passed away; and still the walls of Londonderry is to the Protestants of Ulster what the trophy of Marathon was to the Athenians”.[1]

Figure 1- The Relief of Derry

On the 7th December 1688, the gates of the city of Londonderry were forcibly closed shut, barring entry to the king’s soldiers seeking admittance, the citizenry openly rebelling against the King. The significance of such an action would have both immediate and long term effects on the future of the city. For the Siege of Londonderry not only represented a clash of armies and ideologies in Ireland, but was the vocal point of a much larger power struggle that encompassed the future of the British crown, and the balance of power in Europe. The idea that this small frontier city on the edge of Europe could somehow wield such consequence may at first appear ludicrous, but when one understands what was at stake, such an idea becomes more plausible. The events leading up to the Siege of Londonderry provide both an interesting backstory to those pivotal 105 days, and the crucial context needed to understand just why it was so important when considering the outcome of the Williamite Wars in Ireland, and the larger conflict raging in Europe against the French King, Louis XIV as part of the War of the Grand Alliance.

The siege, as with any major event of the 17th century within Britain and Ireland, was inextricably tied to affairs of the Stuarts, more specifically, James II, a practicing Catholic. The idea of a Catholic King on the English throne was a most difficult proposition for many to accept, as is evidenced by the series of anti-Catholic propaganda policies, hysteria and exclusionist policies, such as the Popish Plot of 1678, The Test Acts and the Exclusion Crisis during the reign of James’ brother, King Charles II. However, nothing came of the campaign to prevent James’ accession, thus meaning England would have it’s first (and last) Catholic King in over a century. Most importantly, James reneged on the Test Acts, thus allowing Catholics serve in high ranking positions in civil and military life. James would actively pursue a policy of “Catholicization” of his realm, restoring Catholics to positions of influence within the Privy Council, Parliament, the army, and navy, traditionally held by Protestants. This fundamentally turned a Protestant army into a largely Catholic one within a year of James’ reign. This would be very much echoed in Ireland. By 1686, the religious denomination of the army in Ireland was roughly 67% Catholic.

Thus, the Protestant establishment therefore tolerated their Catholic King given that his daughter, and apparent heir, Mary would succeed her father as a Protestant monarch. They were not, however, prepared to tolerate a male, Catholic heir. James’ Catholic wife, the Italian, Mary of Modena, gave birth to a boy on the 10th June 1688, giving arise to the “warming pan” myth. This was the straw that broke the camel’s back. Essentially, this meant that Mary was supplanted as heir to the throne, thus allowing for a dynasty of Catholic monarchs to rule the three kingdoms.

Additionally, after putting down two anti- Catholic rebellions, (Monmouth and Argyll) James increased the size of the standing army considerably, causing much fear amongst the Protestant elite of a “Catholic takeover”. Come the end of 1685, the English army numbered in the region of 20,000 men. Furthermore, James issued the Declaration of Indulgence of 1672, which proposed public worship for all denominations of the Christian faith. The seven Anglican Bishops who rejected this proposition were imprisoned, further adding to fears of the erosion of Protestantism within public life. It must be remembered that Protestantism, more specifically, Anglicanism, made up the social fabric of 17th century England. Any attempt to dismantle this dominion of power was unacceptable. James was seemingly unconcerned with alienating the established church that would ultimately lead to his downfall. With James unable to implement his policies of Catholic toleration through Parliament, he would do what his father had done four decades earlier; prorogue Parliament, and assume absolute power. For the second time in 17th century England, a Stuart monarch would come to blows with his Parliament.

On the 10th July 1688 (old style) an invitation was sent to William, Prince of Orange by the “Immortal Seven”, a coalition of leading members of Parliament, and made up of both Whigs and Tories. Such was the mindset of these men that they would rather have a foreign born, Protestant King, than an English born, Catholic King. They asked William, who was married to James’ daughter, Mary, to assume the thrones of England, Scotland and Ireland. With James’ disastrous response on the Salisbury Plains, later fleeing to France, the Convention Parliament declared James had abdicated his throne, and proclaimed William and Mary as joint monarchs, being crowned on the 21st April 1689 . Whilst William’s accession to the throne, and the Glorious Revolution by in large went by with little opposition, his control over the three realms was not entirely secure. The most pressing was Ireland, where James II was still technically king. On the 12th March 1689, under pressure from his cousin, the French King, Louis XIV, James would make for Ireland, arriving in Kinsale, Co. Cork. Controlling Ireland was of utmost importance for James. For if he controlled Ireland, he could make a serious attempt to regain his throne by using Ireland as a steppingstone to reclaim Britain. Upon his arrival, James would be greeted with a significant degree of support from Ireland’s majority Catholic population, in part due to historical context e.g Catholics sided with James’ father, King Charles I during the 1641 rebellion, and the Irish Confederate Wars 1642-1653. Furthermore, the actions of Richard Talbot, (also known as “lying dick Talbot”) Earl of Tyrconnel played a crucial role in drumming up support for James. Talbot had pursued a most swift strategy of purging Protestant soldiers and officers from the Irish army. Roughly in the region of some 4,000 Protestant were removed, to be replaced by Catholics on the grounds that were “Old Cromwellians”.

If the rapid removal of Protestants within the army gave rise to the notion of persecution against the Protestants of Ireland, the discovery of the Comber Letter all but confirmed this in their minds. The letter was discovered in the small County Down town of Comber, addressed to Hugh Montgomery, Second Earl of Mountalexander. The letter warned of an imminent massacre of Protestants across Ireland;

“I have written to you to let you know that all our Irishmen through Ireland is sworn; that on the ninth day of this month they are all to fall on to kill and murder man, wife, and child”.[2]

Whilst almost assuredly a hoax, the letter spread like wildfire across Protestant Ireland, with the memories of the 1641 rebellion still fresh in the minds of Ulster Protestants. A diarist and clergyman present during the siege commented;

The memory of the miseries of ’41 was fresh, and they were loath to trust themselves now in the same hands that seemed to have now more power and better pretence to act those barbarities over again[3]

The letter would reach Londonderry on the 7th December, upon receival by Alderman John Tompkins, and the former Governor of Londonderry, Colonel George Phillips, then residing in Newton Limavady. Phillips sent two messengers to Londonderry warning of the arrival of the Earl of Antrim’s regiment to replace the recently departed and largely Protestant regiment of William Stewart, 1st Viscount Mountjoy, of which Tyrconnell had ordered to leave Londonderry for Dublin only a couple of weeks prior on the 23rd November 1688, deeming them to be too unreliable for such an important posting. They were to be replaced by the regiment of Alexander MacDonnell, Earl of Antrim, which comprised of “six to eight” companies of Irish Glensmen and Scottish Highlanders, known as the “Redshanks” and numbering somewhere in the region of 1,200 men. The Reverend George Walker in his diary of the siege would write;

It pleased God so to infatuate the Councils of my Lord Tyrconnel, that when the three Thousand Men were sent to England to assist his Master against the Invasion of the Prince of Orange, he took par- ticular care to send away the whole Regiment Quartered in and about this City ; he soon saw his Error, and endeavoured to repair it, by Commanding my Lord Antrim to Quarter there with his Regiment, consisting of a numerous swarm of Irish and Highlanders[4]

The Redshanks reached Newton Limavady on 6th December, 20km outside of Londonderry. Phillips’s message reached the city a day later on the 7th, with the courier stating he had passed Antrim’s regiment 3km from the River Foyle. Phillips’ second letter advised the walled city to shut its gates, assuming that the Redshanks were to be the perpetrators of the massacre mentioned in the Comber Letter[5]

With the 9th December fast approaching, the inhabitants of Londonderry were faced with a stark decision. They could either admit the Redshanks into the city, risking the foretold massacre, or they could shut the gates as warned to by Colonel Phillips. However, such an action would be outright treason, as the Earl of Antrim’s regiment was acting upon the orders of Tyrconnel, the King’s Lord Deputy in Ireland. There was a tremendous level of fear that Antrim’s Regiment would replace the largely Protestant regiment that had been garrisoned within the city with a Catholic one. Mackenzie writes,

The Lord Mountjoy’s Regiment of Foot (a well disciplined battalion) was then garrisoned in and about Londonderry and their colonel, several of the officers, and some of the soldiers being Protestants, the inhabitants of that city looked on their being there as a great security to them, and dreaded the thoughts of their removal.[6]

The Bishop of the city, Dr Ezekiel Hopkins warned against denying entry to Antrim’s Regiment, citing such an action would be an affront to God and his divinely appointed King. The 7th December saw the arrival of three companies of Antrim’s Regiment, commanded by a lieutenant and an ensign, reach the Foyle’s east bank. Furthermore, they were ferried across and welcomed into the city by the Deputy Mayor, John Buchanan and Sheriff Kennedy.[7] A contemporary poem featured within Aicken’s Londerrias, offers an insight to Hopkins’s frame of mind;

Dear friends, a war upon yourselves you’ll bring:

Talbot’s deputed by a lawful king;

They that resist his power do God withstand.

You’ll draw a potent army to this land[8]

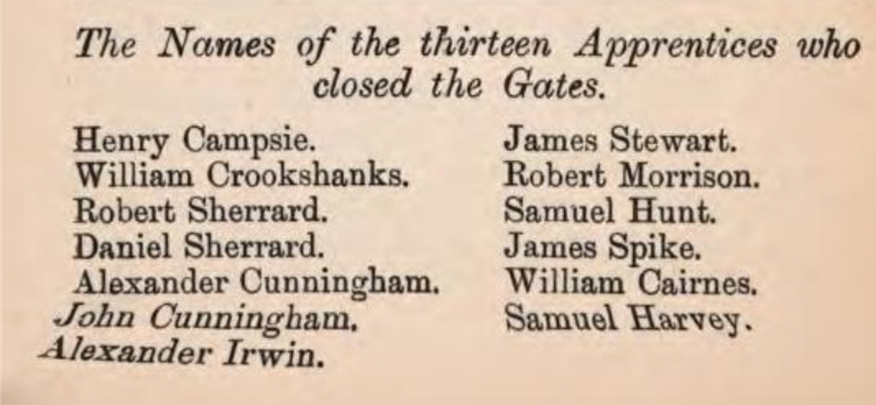

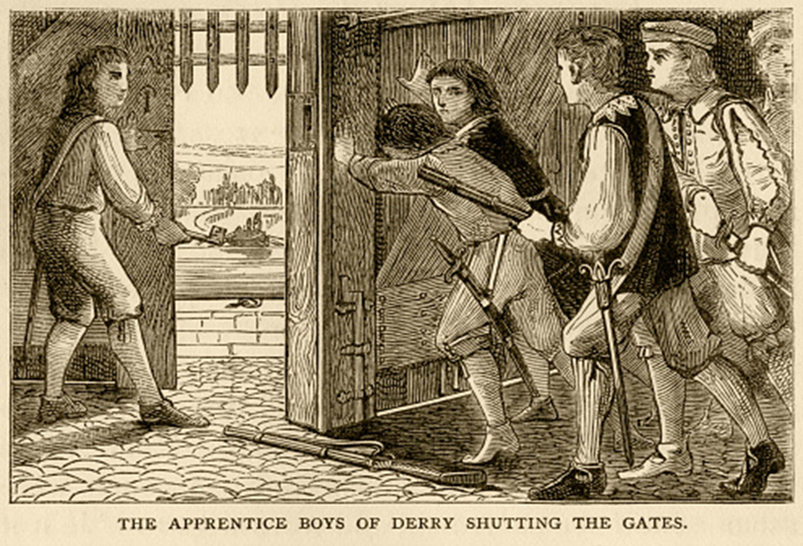

Upon witnessing this event transpire, a group of young men, nine in number, later to be joined by an additional four to their group of apprentices, raised their swords and seized the keys to Ferry Gate, hauled up the drawbridge before finally slamming shut the gate. History would come to know these young men as the “Apprentice Boys”. Their names were as follows;

The motives of The Apprentice Boys are uncertain, but we can assume they were inspired, or at least encouraged, by the outspoken Presbyterian Minister, Reverend James Gordon who had repeatedly called for the gates to be shut. As Mackenzie states;

Mr Gordon, a Nonconformist minister, what was expedient to be done, who not only advised to the shutting of the gates, but wrote that day to several neighbouring parishes to put themselves into a posture assisting the city[10]

Furthermore, Mackenzie records that a citizen by the name of James Morrison stood upon the walls of Ferry Gate, and proceeded to shout toward the Redshanks below;

The Irish soldiers in the meantime, stood at the gate, fretting at their present disappointment, that they should be forced to wait like scoundrels, where they hoped to domineer as lords, till one, Mr. James Morrison, a citizen, having in vain warned them to be gone, called aloud, “Bring about a great gun here”, the very name whereof sent them packing in great haste and fight to their fellows on the other side the water[11]

Regardless of the authenticity of such a statement, the Redshanks camped outside Ferry Gate crossed the east bank of the Foyle, and returned to their regiment. With one regiment seemingly fended off, another came to be regarded with great suspicion by the citizens of the city. The once lauded regiment of Mountjoy had returned to Londonderry from Dublin at the behest of Talbot;

“to use our endeavours with the citizens of that place to receive us as a gareson”[12]

Figure 5

Additionally, Mountjoy’s regiment now consisted of a large number of Roman Catholics, further adding to the suspicions of the citizenry, combined with the unfavourable martial situation of the city. Mackenzie writes that whilst the city was “protected by a good guard” upon the walls;

8th December, since they wanted both arms and ammunition, they broke open the magazine, and took out thence about 150 muskets, with some quantity of match, and one barrel of powder, and bullets proportionable. There was in the magazine at that time but eight or nine barrels of powder in all, and about two more in the town (two or three of those were not fit for use). There were but few arms fixed, and those designed for the Irish regiment, the rest, being about a thousand more, were much out of order.[13]

The arrival of Mountjoy’s Regiment to the walled city introduced one of the siege’s most infamous of figures, Lieutenant-Colonel Robert Lundy. Lundy enters this great epoch of Irish history accompanying Lord Mountjoy, who along with 6 of his companies, rode to Londonderry, arriving on the morning of 21st December, upon which demanded entry via Bishop’s Gate. Talks between Mountjoy and the city elders were instigated, with an amicable arrangement being made between the two parties. To surmise, the agreement stated that companies of Lieutenant Colonel Robert Lundy and Captain William Stewart would comprise of solely Protestant soldiers, and would be permitted to quarter within the city. Additionally, Lundy would take up the mantle of Governor of Londonderry. Lundy would enter the city on 22nd December with his two companies, with further agreement being made that no other companies should enter the city before 10th March.

Lundy’s main task after having been appointed Governor was to oversee the defences of the city. Action against the rebels in Londonderry was now certain, and responsibility fell upon the Governor to prepare for whatever eventual action may befall the city. Lundy was quick to highlight the inadequacies of the city’s defences.

The instructions given to Lundy stressed the importance of preparing the city in the eventuality of a potential Jacobite attack. This included tasks such as; furnishing the garrison with provisions and ammunition needed for their defence, break down bridges leading to the city, cut dykes. Increased attention was given to the city gates, guns and their carriages, with additional works being made on the city walls and fortifications. Furthermore, Lundy was to erect palisades where necessary. Lundy would also note that the walls were;

misirably out of repair and surrounded with dunghills as High as themselves[14]

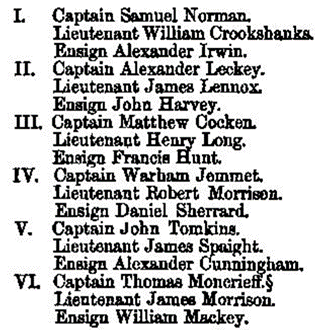

Furthermore, Lundy formed six new companies, adding to the five already raised within the walls by David Cairns. Mackenzie in his account records the recently formed companies;

With Lundy preparing Londonderry for an inevitable assault, the Irish Jacobite forces, accompanied by their French allies, controlled much of Ireland, including large swathes of Ulster. Under the command of Lieutenant General Richard Hamilton, the Jacobites won a series of victories, most notably on the 14th March 1689 with “The Rout of Dromore” in the small County Down town of Dromore. Eastern Ulster would fall into Jacobite control, of particular importance, Lisburn, Hillsborough, Carrickfergus and Belfast. The Protestant forces under Sir Arthur Rawdon were vastly outnumbered by their Jacobite foes, who captured Hillsborough Castle.[16] The “Protestant Army of the North” was now confined to the walled cities of Enniskillen and Londonderry.

With much of Ulster in dire straits, Lundy would make another significant contribution to the defence of Londonderry by ordering a mass retreat of Protestants from Dungannon, Cavan, Coleraine and Monaghan to the walled city. The roads leading to the Londonderry were filled with Protestant refugees, for it was only Londonderry and Enniskillen that provided any hope of resistance to King James’ army. Droves of Protestants crossed the topography of northwest Ulster, where they finally reached their haven of Londonderry. By the time the final streams of refugees made their way into the city, the defences had improved tenfold. Lundy’s efforts were of the utmost significance. His experience in siege warfare gained during his time in Tangier with the Royal Regiment of Foot was of invaluable importance to the defenders of the city. [17] He recognised the sophistication of the French military engineers within the Jacobite ranks, thus how best to defend against such a foe. Lundy made a number of last-minute decisions to bolster the city’s defences further; levelling of the suburbs, completing the ravelin and bringing in additional provisions to the city. Furthermore, a large gun was brought to Londonderry from the nearby Culmore Fort by order of Colonel Lundy. Additionally, Captain Thomas Ash, in his journal of the siege, comments on Lundy’s efforts to further prepare the city’s defences, ordering the houses next to the Waterside to be burned to the ground. [18]

The presence of Jacobite forays to the outskirts of the walled city become more frequent. On the 13th April, Ash records that; “A considerable party of King James’s army came near the Waterside of Derry, and fixed a cannon on the bastion next Ferrygate, but did no execution… The enemy again drew off and encamped at Ballyowen that night”.[19] With the alarming Jacobite vanguard sightings from the walls, it was decided by the Council of War that a more proactive approach was to be adopted. Mackenzie writes;

all officers and soldiers, horse, dragoons and foot, that can or will fight for their country and religion against Popery, shall appear on the fittest ground near Cladyford, Linford, and Longcausey, as shall be nearest to their several and respective quarters, there to draw up in battalions to be ready to fight the enemy.[20]

By the 14th April, James’ Generals, Richard Hamilton and Jean Camus, the Marquis de Pusignan, would reach Strabane, a mere 15 miles south of Londonderry. For the Jacobite forces to arrive at the walled city, they had to cross the west bank of the River Foyle, which included crossing the passes where the Foyle begins, with the two smaller rivers of the Finn and the Mourne. The first series of engagements of the siege would occur several miles from the city of Londonderry with the passes of these rivers manned by Williamites, who were ordered to bring with them a week’s worth of provisions. They made a considerable effort to secure the crossing at the River Finn, having repelled any Jacobite advances across the ford. The following day, Lundy would led the core force of his army out of the city, to further repel the Jacobites at Lifford and Claudy. The size of Lundy’s force varies in estimation anywhere from 5,000-10,000 men, the number being reinforced on its march to Lifford. Jacobite General, Richard Hamilton estimated there were in the region of 10,000 rebels on the banks of the Finn, where he crossed with three squadrons of cavalry, two of dragoons and 1,000 strong infantry.

So it was on the 15th April that two Jacobite cavalry vanguards, lead by Richard Hamilton and Rosen, attacked the Williamite defences on the passes, with Hamilton attacking those of Castlefinn and Clady. Whilst the pass at Castlefinn was successfully defended by Colonel Clotworthy Skeffington’s regiment, commanded by Mitchelburne. Additionally, Colonel Adam Murray, commanding Stewart’s regiment of thirty dragoons, held back the Jacobites “until their ammunition was spent”.[21] However, Claudy was a disaster for the Williamite defenders. Those Williamites that made it to Claudy were a disorganised rabble to put it bluntly. The officers were confused in their objectives, the soldiers untrained, there was little in the way of ammunition and a mixture of antique muskets, pitch forks and scythes, made any attempt of a serious Williamite defence unlikely.[22] Lundy’s men made a general retreat to the city, paving the way open to Londonderry for the Jacobites. It is with this failure that ultimately proved to be the downfall for Lundy. Ash would write,

The enemy came over at Claudy-ford without much opposition, although there were five to one against them, which caused suspicion that Colonel Lundy was a traitor to our cause; for had he marched our army on Sunday the fourteenth, the enemy had not all probably so easily gotten over”.[23]

Ash was not alone in his accusations against Lundy. David Cairns, who had just returned from a trip to London, where he successfully guaranteed supplies and means of support from King William for the city’s defence, was dismayed to find crowds of men and officers leaving they city in a panicked state, “Colonel Lundy had offered passes to the officers, and spoke so discouragingly to many of them, concerning the indefensibleness of the place, that they strongly suspected he had a design to give it up”[24],thus suggesting treachery on Lundy’s part to Cairns.[25] Furthermore, Mackenzie records how Cairns repeatedly warned Lundy for the need to be hasty in preparing the defences of the passes;

The body of the enemy’s army marched up towards Strabane, part of them within view of the city, whereupon Mr Cairns went twice to Governor Lund, pressuring him to take some speedy effectual care for securing the passes of Fin Water, lest the enemy should get over before our men could meet. He replied in a carless manner that he had given orders already, but how little was actually done towards the prevention of it the next day gave us a sad demonstration. The same day several others sent word to Governor Lundy, that if he did not march the men that day, the enemy would certainly prevent their getting together in any orderly body. But their advice was not regarded.[26]

Events would take another turn with the arrival of King James before the walls. James, who had by now joined his Irish Jacobite army, made his way to Londonderry from Dublin, leaving on the 8th and making his way north via Armagh, Charlemont and Dungannon before finally reaching the walled city on the 18th April.[27] James, who, according to the Duke of Berwick had been reassured by Rosen that his presence alone would cause the defenders behind the walls to see the error of their ways, and immediately lay down their arms, would present himself before Bishop’s Gate. However, unbeknownst to James, an agreement had been made between the defenders of the city and Richard Hamilton that no Jacobites would come within “four miles of the city”.[28] To their great surprise, the King himself appeared before the walls. With confusion reigning, the Williamites fired upon James;

But our men on the walls paid so little deference to either them or their orders, and so little regarded the secret treaties they were managing with the enemy, that when King James’ forces were advancing towards them on the strand, they presently fired their great guns at them, and, as was confidently reported, killed one Captain Troy, near the King*s person. This unexpected salutation not only struck a strange terror into the Irish camp, but put ;the King himself into some disorder, to find himself so roughly and unmannerly treated by those from whom he expected so dutiful a compliance.[29]

Lundy’s time as governor of Londonderry came to a rather bitter end. With the failure to adequately defend the passes, the mood within the city turned sour, and prior suspicions of Lundy’s intentions of surrender became outright accusations of treachery. Colonel Adam Murray, who had been at Culmore Fort, received an express letter outlining Lundy’s plans to surrender the city to James, made great haste to Londonderry, before finally confronting Lundy. Mackenzie details this interaction between the two men as follows;

This same council this day proceeded to conclude a surrender, and drew up a paper to that purpose, which most of them Signed, and as far as I could ever leam^ all of them

But to return to Captain Murray, the multitude having eagerly desired and expected his coming, followed him through the streets with great expressions of their respect and affection. He assured them he would stand by them in defence of their lives and the Protestant interest, and assist them immediately to suppress Lundy and his council, to prevent their design of surrendering the city ; desiring all who would concur with him herein, to put a white cloth on their left arm, which they generally did, being also encouraged to it by Captain Bashford, Captain Noble, and others. This greatly alarmed and perplexed the Governor and his council They conclude to send for him, and try if they can prevail with him to sign the paper for surrendering the city.

Captain Murray told him plainly his late actions had declared him either fool or knave : and to make this charge good he insisted on his gross neglect to secure the passes at Strabane, Lifford, and Clady, refusing ammunition when sent for, riding away from an army of ten or twelve thousand men, able and willing to have encountered the enemy, neglecting the advantageous passes of Longcausey and Carrigins, which a few men might have de- fended, &c. He urged him to take the field, and fight the enemy, assuring him of the readiness of the soldiers, whom he vindicated from those aspersions of cowardice which Colonel Lundy cast on them ; and when Colonel Lundy persuaded him to join with the gentlemen there present, who had signed a paper for surrendering the town, and offered several arguments to that purpose, drawn from their danger ; he absolutely re- fused it, unless it were agreed on in a general council of the officers, which he alleged that could not be, since there were as many absent as present[30]

Lundy’s time was up, as Ash writes, “Colonel Lundy deserted our garrison, and went in disguise to Scotland, and by this proved the justness of our former suspicions”.[31] A new Governor was needed, and with the popular choice of Colonel Adam Murray refusing, “because he judged himself fitter for action and service in the field, than for conduct or government”.[32] The duty to see the city through the siege fell upon Colonel Henry Baker, and Reverend George Walker, who were elected as joint Governors on the 19th April. They divided the city into sectors and assigned a regiment to each sector. Two cannon are mounted on the tower of St Columb’s Cathedral, facing south towards the Jacobite lines with the remaining cannon placed along the walls.

Figures 6-9

[1] Macaulay, T.B The History of England from the Accession of James II (London,1953) p. 58

[2] Mackenzie, J, A Narrative of the Siege of Londonderry (London,1690) , in W.D Killen, Mackenzie’s Memorials of the Siege of Derry, (London,1861) p.8

[3] IDIB

[4] Walker,G Narrative of Siege of Londonderry p.

[5] Childs, J. 2017, The Williamite Wars in Ireland 1689-1691 p. 5

[6] Mackenzie, J, A Narrative of the Siege of Londonderry (London,1690) , in W.D Killen, Mackenzie’s Memorials of the Siege of Derry, (London,1861) p.7

[7] Childs, J. 2017, The Williamite Wars in Ireland 1689-1691 p.6

[8] Londerrias, Joseph Aickin– pg 10

[9] Walker,G Narrative of Siege of Londonderry p.94

[10] Mackenzie, J, A Narrative of the Siege of Londonderry (London,1690) , in W.D Killen, Mackenzie’s Memorials of the Siege of Derry, (London,1861) p.9

[11] IDIB, p.11

[12] Dougherty, R. The Siege of Derry 1689 The Military History (Stroud, 2010) p.33

[13] Mackenzie, J, A Narrative of the Siege of Londonderry (London,1690) , in W.D Killen, Mackenzie’s Memorials of the Siege of Derry, (London,1861) p.

[14] NAS GD26/7/37

[15] Mackenzie, J, A Narrative of the Siege of Londonderry (London,1690) , in W.D Killen, Mackenzie’s Memorials of the Siege of Derry, (London,1861) p13

[16] Witherow, T, Derry and Enniskillen in the Year 1689, 1931

[17]Dougherty, R. The Siege of Derry 1689 The Military History (Stroud, 2010) p57

[18] Ash,T Circumstantial Journal of the Siege of Londonderry, p.280

[19] Ash, T, A Circumstantial Journal of the Siege of Londonderry, 1792, p. 280 &281

[20] Mackenzie, J, A Narrative of the Siege of Londonderry (London,1690) , in W.D Killen, Mackenzie’s Memorials of the Siege of Derry, (London,1861) p.29&30

[21] R. Simpson, The Annals of Derry: Showing the Rise and Progress of the Town from the Earliest Accounts On Record to the Plantation Under King James I. 1613, and … the City of Londonderry to the Present Time (Londonderry, 1847).

[22]Childs, J. 2017, The Williamite Wars in Ireland 1689-1691 p.70

[23] Ash, T, A Circumstantial Journal of the Siege of Londonderry,1792, p. 281

[24] Mackenzie, J, A Narrative of the Siege of Londonderry (London,1690) , in W.D Killen, Mackenzie’s Memorials of the Siege of Derry, (London,1861) p

[25] Cairns, D History of Ireland in the Lives of Irishmen

[26] Mackenzie, J, A Narrative of the Siege of Londonderry (London,1690) , in W.D Killen, Mackenzie’s Memorials of the Siege of Derry, (London,1861) p.29&30

[27]Witherow, T, Derry and Enniskillen in the Year 1689, 1931 p.101

[28] Walker,G Narrative of Siege of Londonderry p.25

[29] Mackenzie, J, A Narrative of the Siege of Londonderry (London,1690) , in W.D Killen, Mackenzie’s Memorials of the Siege of Derry, (London,1861) p.35

[30] Mackenzie, J, A Narrative of the Siege of Londonderry (London,1690) , in W.D Killen, Mackenzie’s Memorials of the Siege of Derry, (London,1861) p.36

[31] Ash, T, A Circumstantial Journal of the Siege of Londonderry,1792, p. 281

[32] Mackenzie, J, A Narrative of the Siege of Londonderry (London,1690) , in W.D Killen, Mackenzie’s Memorials of the Siege of Derry, (London,1861) p38

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.