United States Army and Navy Veteran – John Casey

First published 27 October 2018

Thank you to Michael Noone for the article and updated report on John.

To mark United States Navy Day we would like to share the story of Irish American John Casey. A remarkable man with a remarkable story. John is one of the unknown tens of thousands of Irish Americans who have served in the United States military. In John’s case he served in both the U.S. Army and Navy. We are lucky to have John’s story as he has spent most of his life in Ireland, and is currently living in Roscommon.

US Army and Navy veteran John Casey was born on the 3 August 1926 in Cambridge, Massachusetts, of Irish parents, James P. Casey and Mary F. O’Brien, who had emigrated to the Boston area sometime around the beginning of 1900. John had one brother, James, who was two-years older. Their father enlisted in the Army and served during the Great War. Still suffering from a gas inhaled during the war, he died in the mid-1930s and their mother took the two boys back to her family outside Athlone, Westmeath, Ireland until such time when they could return to the U.S. and the boys could take jobs.

Their plans were interrupted by Germany’s Hitler when he declared war on Poland and World War II began in September 1939. All transatlantic passenger ship traffic came to a halt and the Casey family was stuck in Ireland. Ireland remained neutral and the family were informed by the U.S. Consulate in Dublin to wait and see if the U.S. could guarantee safe passage to the U.S. Germany did allow one passenger ship from Europe to the U.S., but that one ship was full of US citizens from mainland Europe only. In 1942 John’s brother James turned 18, which meant he was eligible to enlist. He joined the U.S. army in Belfast, Northern Ireland. He volunteered as a member of the first American Ranger Battalion, who were trained by the British Commandoes. The unit made history in North Africa, Sicily and the Anzio Beachhead in Italy where he was captured and became a POW.

Following in his brother’s footsteps, John headed for Belfast two years later and enlisted in the American Army. He was sent to England without training and then to France. John remembers well the boat across the English Channel on 7/8 May. As they approached the harbor, the sky lit up. The men sank in dread the Germans had somehow launched a new offensive. As it turned out it was celebrations to mark the unconditional surrender of German forces. In France the new recruits were trained by staff member who came ashore on D-Day. John was then sent to the Bremen Enclave in Northern Germany until he accumulated enough points to return to the U.S. for discharge. John rose to the rank of Sergeant.

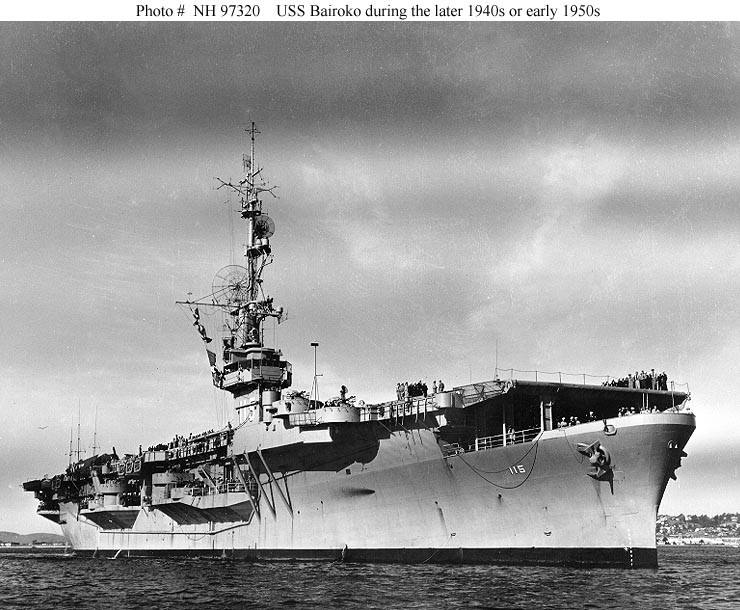

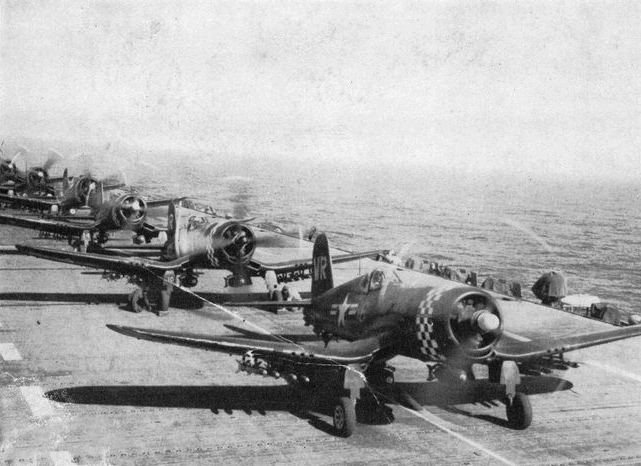

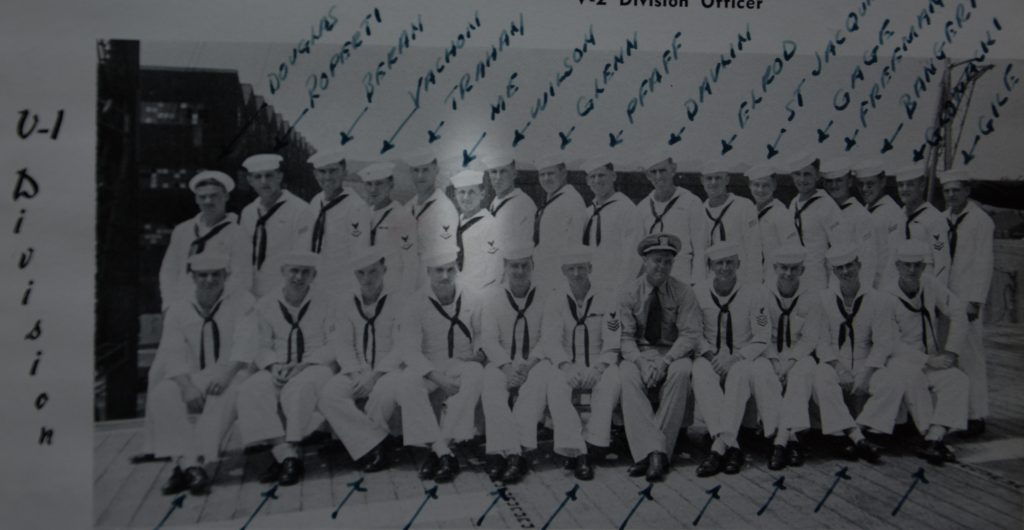

In the U.S. John worked for the Boston Gas Company. He hated the job, hated the civilian life and decided to join the U.S. Navy under a four year enlistment. No boot camp training needed as he held the pay grade of an army corporal. John was sent to the Naval Air Technical Training Command in Memphis, Tennessee where he graduated as an engine specialist and transferred to Naval Air Station Quonset Point Rode Island. His job there was to conduct a “Yellow Sheet” inspection of repaired navy planes for the test pilots; part of which included warming up the engines. While at Quonset Point the Korean War broke out. President Truman immediately tacked on an extra year to John’s enlistment. He was transferred to Alameda California as a member of Ships Company on a “Jeep” aircraft carrier, the USS Bairoko CVE 115 which was brought back into service from the mothball fleet. After getting the ship ready to join the fleet, it was transferred to San Diego, her home port. Finally, with the carrier loaded with planes, marines and equipment for the fighting war with North Korea, she sailed to her overseas “home port” Yokosuka, Japan. John was assigned to the flight deck as a “Yellow Shirt” plane director and guided many pilots to the catapults for launching. When they returned from “in country” John was the fire “Yellow Shirt” to guide the pilots back aboard…….day or night. With an end to the conflict, the Bairoko’s cruise with the 7th Fleet was over and John’s five-year enlistment was coming to an end and John was discharged from the navy.

John took advantage of the GI Bill and spent three years at a government approved school of broadcasting, televising and movie making. He wound up working in Hollywood studios as an assistant film editor for several first run movies and many TV series. John decided to return to Ireland to take care of his mother and set up a photography studio; he is proud of photographing over 900 weddings. After his mother passed away, he met and married a Margaret Leo from Tuam, Co. Galway. Sadly, she died after 18 years from Cancer. John then moved from Athlone to Grange, Co. Roscommon. John who is now 96, is still living comfortably in a nursing home.

We would like to thank John’s niece Kathleen Cummings and the American Legion Post IR03 ‘Commodore John Barry’ for their help in this production.